Superb Roman ruins, glorious scenery, good food and ridiculously low prices – Edward Reeves finds much to admire in the former communist state.

This is odd. I'm sitting in a bar in Tirana, Albania, and there's not a gangster in sight. What there is is a 20ft-long counter packed with an array of enticing meats, a friendly man who grills them on request, and beer at 70p a glass. Everyone speaks English, and everyone is unfailingly nice. Could it be that there's a mismatch between Albania's reputation for – how to put this politely? – unconventional economic activity, and the modern-day reality? After a week travelling the country with my mother, without so much of a whiff of trouble or a gangster's cheap cologne, I'd say the answer is a resounding yes.

In fact, our Albanian trip has turned us both into bores when it comes to this oft-ignored Mediterranean country's virtues as a tourist destination. For those of you with a short attention span, the upshot of this article is "Go!" But first some context.

Our trip came about when I read that tour operator, Voyages Jules Verne (VJV), was returning to the country after a 20-year absence. Back in the late Eighties a VJV trip was the only way to visit Albania, which was ruled by a paranoid communist dictatorship that issued a few hundred visas each year. My intrepid, left-leaning mother went not once, but twice, in 1986 and 1987, flying into Titograd in the former Yugoslavia (now Podgorica, capital of Montenegro) and crossing the border at 3am under searchlights, as wolves howled in the distance. All books, magazines and other printed matter were confiscated by Kalashnikov-wielding guards and visitors had to walk through a sheep dip to kill capitalist germs. Welcome to Albania.

How times change. We fly direct into Tirana to begin VJV's new "Classical Tour of Albania" itinerary – and there's not a sheep dip in sight. The airport is clean and modern, with an even cleaner and more modern tour bus waiting 100 yards from the exit. Our guide, Elton Caushi, could be mistaken for an Italian art student. Young people, he says, acutely aware of Albania's reputation abroad, now avoid the dark, hired-killer look that was thought to be cool in the Nineties.

There's no hanging about – VJV's bumpf makes it clear that Albania's geography and poor road network dictate long coach journeys (and warns there's a fair degree of walking). First stop is the 18th-century monastery of Ardenica, sitting on a hill that the communist regime burrowed into and covered in bunkers and gun emplacements (Albania is peppered with bunkers – there are thought to be more than 700,000 of them). My mother didn't visit Ardenica on her previous trips – back then the church was used as a storeroom for military kit. The survival of its splendid iconostasis and frescoes, by two of Albania's finest icon painters, the brothers Konstandin and Athanas Zografi, is something of a miracle.

We spend the night at the town of Fier which, for the record, smells of petrol (it's near a refinery) and has nothing to offer even the most rosy-spectacled visitor. It's convenient, however, for the ruined city of Apollonia, which we visit the following morning. Truth be told, its most famous resident, Augustus, would be hard-pushed to recognise it.

But we have high hopes for our next historical site, Butrint, scheduled for the following morning. Trouble is, Butrint is far to the south, close to the Greek border. This means a day driving the Albanian Riviera, to Saranda, where we'll stay two nights. And it's a long drive – close on eight hours – but with stops for lunch to enjoy the view from the Llogaraja Pass and the fort built by Ali Pasha (of Byron fame) at Palermo Bay.

|

| Drymades beach, Albanian Riviera |

Scenery aside, the major point of interest is olive trees planted on a hillside to spell the name of Albania's unlamented dictator Enver Hoxha. My mother remembers the hills being festooned with such slogans, in white-painted stones. It was a way of imposing control, Elton explains – trusted communists might be ordered to paint "Enver"; the politically suspect would get phrases such as "United States Capitalist Imperialism is a Paper Tiger", which could take months. My mother looks crestfallen. "I assumed they were painted by grateful villagers," she says.

Butrint, we discover, is a magical site. In Italy it would be packed with visitors; we share it with a single coachload of elderly Germans. The ruins are spread over a small peninsula, and range from the fourth century BC through to the early 1900s (Ali Pasha had a hunting lodge here), via the Byzantine era. Terrapins sunbathe in the flooded theatre and bathhouse, crickets chirrup and eucalyptus leaves rustle gently in the breeze. All in all it's a very satisfactory place to spend a morning.

Next day we drive a couple of hours inland to the town of Gjirokastra. This Unesco World Heritage Site is utterly charming, with steep cobbled streets, crumbling Ottoman houses and a spooky castle. This is closer to the Albania my mother remembers, though with the addition of a small capitalist economy of craftsmen selling wood and stone carvings, and an eccentric shack of a restaurant, Kujtimi, where she's able to tuck into (delicious) frogs' legs.

It's worth mentioning that Albanian cuisine is generally good quality, and refreshingly cheap. Food had been an issue on my mother's last visit – in the Adriatic "resort" of Dürres her half-starved tour group had found just one café, which had to be opened specially by an aged crone who clearly believed everything the Hoxha regime told her about sulphurous Westerners. The menu had the advantage of simplicity: brown bread, served with a snarl.

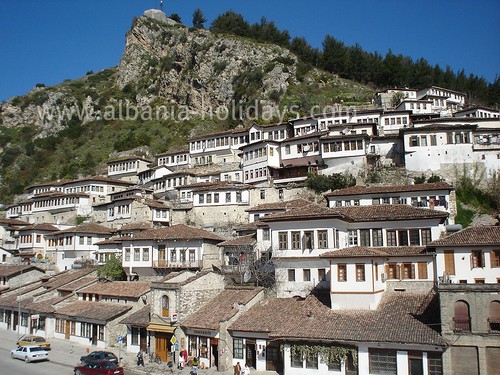

|

| Berat Albania |

Final stop is Tirana, the capital, which turns out to be a friendly, buzzing place. There's too much to see and do in our short stay, which includes a day trip to nearby Kruja, the fortified town from which Albania's national hero Skanderbeg led the 15th-century resistance against the Turks. Enver Hoxha's daughter herself restored the castle and turned it into a shrine to Albanian nationalism. The big change, my mother says, is the cobbled bazaar, which was firmly shut on her last visit (back then VJV recommended £5 spending money for the entire week; all visitors could buy were translations of Hoxha's various masterworks). The bazaar is now piled high with communist detritus.

That night, in Tirana, we wander around Blloku, the old residential area for the nomenclature. Until communism fell, it was out of bounds to ordinary Albanians. Now it's packed with bars, cafés and fashionable young people having fun.

|

| Tirana, Albania |

My mother proclaims she's going to come back and explore the north of the country, solo, at a more leisurely pace. She's sad that the socialist experiment failed, but her opinion of Albania – and Albanians – has changed completely.

"I used to think they were a dour, unsmiling bunch," she says, "but now they're all so friendly." Funny that.

Did you know?

Last year, Lonely Planet made Albania number one of its world's top 10 places to visit.

GETTING THERE

British Airways ( 0844 493 0787 ; ba.com) flies direct from Gatwick to Tirana from £157 return.

PACKAGES

Voyages Jules Verne ( 0845 166 7035 ; vjv.com) offers a seven-night Classical Tour of Albania from £895 per person, taking in Tirana, Saranda and Butrint, Gjirokastra, Berati and Kruja, including international flights, transfers, accommodation with two evening meals and breakfast daily. Alternatively, consider its three-night A Taste of Albania package, from £495.

WHEN TO GO

As with most Mediterranean destinations, spring and autumn are the best times to visit. If you’re visiting the Riviera, July and August see a big influx of visitors from elsewhere in the Balkans.

THE INSIDE TRACK

Forget all the clichés about Albanian gangsters – street crime is practically unheard of and you’re extremely unlikely to encounter any problems such as pickpocketing. Compared with any British city, Tirana feels incredibly safe – provincial cities even safer. Hotels are keenly priced, but there’s a shortage of quality accommodation. Expect eccentric décor and sometimes shambolic service. If you’re booking in Tirana, avoid hotels in the Blloku district. There’s always the chance you’ll find yourself next door to the latest club, with thumping bass until the early hours. Eating out is cheap by British and Eurozone standards, especially once you’re out of Tirana. Typical prices might be £1.15 for a salad or starter, £1.70 for a pasta dish, £3.40 for a meat dish and 90p for a pudding. Albanian wines were drinkable, even under communism, and are getting better and better every year. Generally a half-litre carafe of house red in a restaurant will be in the region of £2. If you want to splurge on a bottle, the finest, reputedly, is Cöbo’s Kashmer. Driving in Albania should hold no fear for competent drivers. However, the roads are often in a terrible state so opt for a 4 x 4 if your budget allows (though along the Riviera a hatchback will be fine). A nasty surprise is the price of petrol, which is comparable with Britain.

WHAT TO BRING HOME

If it’s on your itinerary, Kruja is the best place to do your shopping, with a bazaar selling kilims, handicrafts and communist memorabilia. The one Albanian universal seems to be homemade lacework, which local women sell at pretty much every (urban) historical site. Beautiful brass coffee grinders were made in Tirana until the fall of communism, and battered but functional ones can be picked up for around £5-£7, depending on condition. Look for the “Made in Albania” imprint on the bottom. Someone, probably Chinese, appears to be making replicas – they’re easily identifiable as they look brand new and have red Albanian flag stickers on the bottom. These sell for an outrageous €27 (£21) at the airport. Books by Enver Hoxha make great gifts, but English translations are collectors’ items (and priced accordingly). Other titles, such as Agriculture in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, at about £15, have wonderfully grainy pictures of fields, “hero” tractor drivers and scientists holding vegetables, accompanied by unintentionally hilarious captions. They’re not going to print any more socialist propaganda, so buy now to avoid disappointment. In Tirana there’s a great jewellery store selling semi-precious stones and tasteful silver jewellery, Koralia, on Rugga Abdyl Frashëri. Don’t expect anyone to speak English, but if you point at the stones you like, and then your ears, eventually the chap behind the counter will make you a pair of earrings on the spot, from about £5. A note on bargaining – you’re not in Morocco and the opening stated price is rarely extortionate, so bear that in mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment