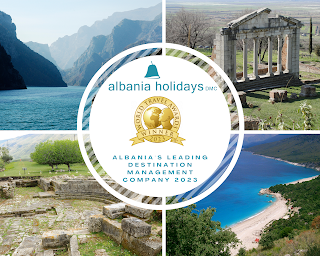

Albania Holidays DMC has been awarded as Albania's Leading Destination Management Company for 2023 by the renowned World Travel Awards™.

17 October 2023

Albania Holidays DMC is awarded as Albania's Leading Destination Management Company for 2023

11 August 2023

10 ristoranti da non perdere in Albania, il nuovo Salento

La meta del 2023? È l’Albania. Il Paese balcanico è la destinazione ideale per passare le proprie vacanze estive (e non): è vicino all’Italia, ben collegato e ricco di sorprese. È la meta ideale anche per un viaggio gastronomico. Da nord a sud sono tanti i ristoranti, gli agriturismi e le taverne dove assaggiare piatti tipici, sapori gustosi e rivisitazioni in chiave contemporanea. Ecco i 10 indirizzi da non perdere se andate nella Terra delle Aquile.

Gli indirizzi dei migliori ristoranti dell'Albania

Padam

Tirana

Lo chef Fundim Gjepali, a capo anche dell’Antico Arco di Roma, ha ideato un menù gustoso e raffinato con piatti che sembrano delle piccole opere d’arte. Tra tutti, da provare l’uovo con tartufo, salsa di yogurt e broccoli, e il gelato artigianale con biscotto pressato.

Lo chef Fundim Gjepali, a capo anche dell’Antico Arco di Roma, ha ideato un menù gustoso e raffinato con piatti che sembrano delle piccole opere d’arte. Tra tutti, da provare l’uovo con tartufo, salsa di yogurt e broccoli, e il gelato artigianale con biscotto pressato.

Tirana

Gzona

Tirana

Nel cuore di Tirana, il giovane chef Bleri Dervishi – uno dei nomi di punta della nuova generazione, con un ricco curriculum di esperienze italiane e internazionali - prepara piatti gourmet con ingredienti e sapori locali. Dalle tartare di manzo e melanzane, passando per le insalate del giorno fino ai dolci, tutto è preparato con maestria.

Fustanella Farm

Tirana

Nel borgo di Petrelë, a una manciata di chilometri dal centro di Tirana, questo ristorante farm-to-table è un gioiellino immerso nella natura dove si va per mangiare prodotti a km 0 e piatti tipici della gastronomia locale e delle comunità albanesi che vivono fuori dai confini nazionali.

Mrizi i Zanave

Fishtë (Lezhë)

Questo tempio della gastronomia albanese, nato da un’idea dei fratelli Prenga, è una tappa irrinunciabile durante un viaggio in Albania. Ai tavoli di Mrizi i Zanave si mangiano formaggi, torte salate, salumi, pasta tipica, spiedini di carne e gustosi dolci. Da annaffiare con i loro vini, che quest’anno hanno vinto ben tre medaglie alla competizione Decanter.

Tradita e Beratit

Berat

La città patrimonio Unesco di Berat, una delle destinazioni più visitate d’Albania, è nota per le sue case tradizionali molte delle quali convertite in guesthouses e ristoranti. Come Tradita e Beratit dove si mangiano byrek, torte salate farcite di spinaci, carne o formaggio, insalate dell’orto, olive, peperoni, ammirando il panorama.

Alpeta Agroturizëm & Winery

Roshnik

A pochi km da Berat, Agroturizëm Alpeta è un agriturismo e cantina ai cui tavoli sono servite verdure dell’orto, torte salate ripiene di spinaci, ricotta salata, porri, carne di capra che vive e cresce sulle pendici del Monte Tomorr, a due passi, casseruole di jufka, pasta fatta a mano e condita con pollo di campagna. I vini, e liquori, sono tra i migliori d’Albania.

Villa Përmet

Përmet

Questa affascinante villa di fine Ottocento, ristrutturata nel minimo dettaglio, è il posto perfetto per assaporare il meglio della gastronomia di Përmet. Il ristorante gourmet al piano terra propone agli ospiti una cucina autentica, stagionale e rispettosa delle tradizioni dove primeggiano verdure dell’orto, carni di animali allevati nella zona, salumi fatti in casa e gliko, un composto a base di frutta tutelato da Slow Food.

Taverna Vasili

Korçë

È il regno dei carnivori: la carne cotta al cognac e il goulash sono prelibati, ma nel menu non mancano carne alla griglia, salsicce, polpette tradizionali. Ottimi anche gli antipasti con peperoni rossi e ricotta salata e i dolci della casa.

Restorant Bujar

Vlorë

Nel menù di Bujar spiccano paccheri con cozze, calamari e pomodorini, catalana con il pescato del giorno e polpo grigliato. Si gustano quasi al naturale, il tutto è cucinato semplicemente, su piastre roventi e servito con olio d’oliva, una spruzzata di limone, sale. In bocca il sapore del Mediterraneo.

Source: www.gamberorosso.it

03 May 2023

Albania's developing tourism industry could help stop its young people from leaving – and boost its economy

It has been more than 30 years since Albania opened its doors to tourists, but telling a friend that you’re off to Tirana or Dhërmi for a long weekend might still raise some eyebrows.

Despite Albania making Lonely Planet’s 2023 best in travel list, and various travel specialists referring to the country as the Mediterranean’s “hidden gem” because of its pristine coastline and wildlife, Albania remains one of the least visited countries in Europe.

Despite its small size, Albania’s varied landscape offers an array of touristic opportunities. Its Adriatic coastline is home to beautiful beaches, not yet spoilt by hordes of visitors.

The interior of the country is wild and mountainous, boasting 15 national parks, picturesque remote villages and breathtaking alpine scenery. At the crossroads of various Mediterranean, Balkan and Ottoman empires, as well as having a history of communist rule, Albanian culture is a mixture of European and Middle Eastern influences, which remains evident in its cuisine and architecture.

So could tourism be an economic saviour for Albania and mediate the migration of its young people? Although visitor numbers are on the rise, the country is facing economic difficulties.

There are now “ghost towns” throughout the country. Kukësi in the north of Albania has seen more than 53% of its citizens leave, with reports showing that young people feel there are few opportunities for them.

According to a 2021 Gallup poll, 50% of Albanian adults wanted to move abroad, with unemployment, low wages and lack of opportunities being listed as main reasons.

In 2022, the United Nations Development Programme assessed Albania’s tourism trends and performance, finding that mass emigration is a significant challenge to the country’s tourism development. Around 75% of the hotels polled claimed that in peak season they would need at least 35% more employees than they are currently able to find.

Industry professionals in Albania feel that infrastructure, waste management and transport links are not at the level required to attract a large number of tourists.

Transformation through tourism

Many countries have used tourism for economic development. After the second world war, tourism became a crucial way for many poorer Mediterranean countries to kickstart their economies.

In 1951, the Greek National Tourism Organisation embarked on a nationwide development initiative to construct tourist facilities across the country, the Xenia project. Renowned Greek architect Aris Konstantinidis was enlisted to design dozens of hotels, bars, souvenir shops and other attractions across the country, in the minimalist whitewashed style Greece is renowned for.

Greece’s image was transformed into a hub for international travellers. At the start of the project, Greece hosted just 33,000 tourists a year – by the 1960s, that figure had increased by 1,098%. Today, tourism accounts for one-fifth of its economy.

A similar strategy was used in Spain. An impoverished, isolated state at the end of the second world war, tourism transformed the Spanish economy. Not only did tourism provide an invaluable source of foreign currency, but the sudden influx of foreign visitors undermined the Franco regime’s grip on the country.

The arrival of international visitors sparked a cultural transformation, as ordinary Spaniards interacted with tourists they began to question and challenge the authoritarian control of Franco’s government. The introduction of tourism is often cited as the catalyst to the toppling of the authoritarian regime.

A growth in Albania’s tourism might offer young people alternative opportunities to those they seek by leaving their home nation. Travel and tourism employ more young people (14- to 25-year-olds) than any other sector, according to a World Travel and Tourism Council study.

And in tourism-dependent countries, jobs tend to become full time and permanent, appealing to people looking for financial stability.

Stunning landscapes

Albania has many of the elements required to become a successful tourist destination. It’s a beautiful country with good food and a wonderful summer climate. In 2022, a TikTok trend sparked a boom in tourist bookings after people posted images of its stunning beaches.

But there are some challenges. For small and underdeveloped destinations like Albania, which may not have the infrastructure required to extensively develop tourism alone, help from outside investors is necessary - and that can come with its own issues.

While mass tourism can bring tourists, new hotels and restaurants, if developments are not locally owned the financial rewards may have limited benefit to the local economy, although they still provide jobs.

The World Travel and Tourism Council found that the Caribbean’s tourism sector suffered from economic leakage of 27.5% in 2019. Journalist Polly Pattullo said that on some islands this figure could be as high as 90%.

This means that this tourism-generated revenue leaves the Caribbean and does not contribute to the economy, due to hotels and tour operators being owned and controlled by foreign companies.

Perhaps Albania could take inspiration from neighbouring Montenegro, which seems to be successfully welcoming tourism. Like Albania, it is not a member of the EU, and has struggled with economic development.

The country has positioned itself as a niche destination. Tourism now accounts

for around 25% of Montenegro’s GDP (compared to around 8% in Albania).

Albania has a falling birthrate, and a struggling economy. For decades, the country sealed its population inside its borders, but these days many young people are desperate to leave. But an improvement in economic prosperity and jobs in the tourism industry might be a significant factor in changing that, if managed well.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: https://uk.news.yahoo.com/albanias-developing-tourism-industry-could-112036715.html?guccounter=1

03 March 2023

In Albania's Tourism Revival, Food Plays a Central Role

After a century of unrest, Albania's welcome remains undimmed as refugees return to piece its national identity back together one dish at a time.

As I stroll the rainbow-painted Soviet blocks of Tirana, Gjergj invites me home for lunch. A pensioner in a tweed cap, with a face as smooth and readable as olive wood, he leaves his game of backgammon on a bench beneath the furry talons of Lebanese cedars when he sees me. “I found you,” he quietly declares, insisting that his wife has already set the table. Soon I am seated before a starched tablecloth laden with tart mountain cheeses, glistening pickles, rosemary-spiked lamb, and pomegranates.

After communism, confiscated cooperative land was re-apportioned in tiny parcels; gardens like craft patchworks, hand-sewn together by wattle. “There’s a family behind every ingredient I use, and I know them all by their first names. I get really emotional about that,” says Bledar Kola, alumnus of Le Gavroche, Fäviken and Noma, who gifts bottles of wine to people queuing outside Mullixhiu, his restaurant in the Grand Park of Tirana. Fitted out like an alpine hut, it is the perfect spartan stage for his minimalist revival of the northern highlands’ cucina povera, using ancient fermentation techniques, foraged fruits, and medicinal plants such as purslane and burdock.

Kola fled Albania at the age of 15, first by speedboat to Italy, then as a stowaway to England, clinging perilously to the chassis of a truck, at one point getting dragged along the asphalt. “In London, I had to say I was Italian to get work,” he says. “Otherwise, it was ‘But don’t you Albanians all steal cars?’ I felt I was betraying my country.” Now he proudly delivers Albanian history lessons in eight courses, unearthed national heroes served at desk-like bakers’ tables. After a palate cleanser of Cornelian cherry juice—a glass of cloudy papal mauve—comes trahana, a savoury porridge, and dromsa, Balkan pici pasta still served in Arbëresh communities in Calabria. At the end, there’s boza, the Ottoman fermented cereal-based drink—at once creamy, fizzy, sweet, and sour. After hours, Kola pulls out a label-less bottle made from Shesh grapes, the fruit of Albania’s ancient viticulture revival, as weighty as a Piedmontese red and palpably alive. When I leave, the stars above the Dajti mountains look bloated and seem to blur with meteorite tails.

My head is mysteriously clear when I leave the next morning to drive north to Lezhë province, the epicenter of the new food movement, with Kreshnik Topollaj, a chatty Bektashi Muslim who wears a felt qeleshe hat (“half of a cosmic egg”), tilted on his head with the steez of a rapper. As he talks, the clouds dissipate to a faint flock of geese on the horizon. Outside a boy sells rabbits from the back of his car. Fields are flecked with yellow goldenrod; branches offer pomegranates like the arms of expert jugglers. The drive can be slow, even on this main road to Lake Shkodër on the Kosovan border. The Dinaric Alps loom overhead; toppling stacks of rock daggers and glacial fortresses. Cow herds dither before us, their bells momentarily picking up to trotting tempo.

A lone cloud rests like a volcano plume on the hillside as we pass through Fishtë to Mrizi i Zanave Agroturizëm, dedicated to Gjergj Fishta, beloved early-20th-century friar and national poet. Its owners, brothers Altin and Anton Prenga, started Albania’s Slow Food foundation in part to protect endangered ingredients such as mountain-dried mishavinë cheese, then made by only three families in tribal Kelmend. The brothers worked in kitchens in Italy for 11 years before, in 2006, returning to the home they fled as children; they recall men waving Kalashnikovs in their grandfather’s fields, and still find bullet cases in the vineyards. They built a restaurant rock by rock—a temple to heirloom produce, which now supports more than 400 families; its incense, rosemary-infused woodsmoke from the outdoor oven strung with rosaries of drying chilis. “The most fantastic food comes from people looking after three cows and 10 fruit trees,” says Altin, a 40-year-old as flushed as a Cox apple by outdoor work and evangelical zeal. In 2016, they restored the derelict cottage they were born in: “It was like piecing together our identities again. You have to be proud to be a farmer.”

14 February 2023

13 January 2023

Cette destination européenne proche de Bruxelles vous donnera l’impression d’être aux Maldives

Il ne faut pas toujours aller bien loin pour changer d’air, découvrir le monde et déconnecter totalement. Le staycation en a convaincu plus d’un durant la crise - cette tendance qui consiste à voyager au plus proche de chez soi - à tel point que désormais nos habitudes de voyages se sont vu impactées. Plus questions de partir à l’autre bout du monde et d’exploser son bilan environnemental en prenant l’avion, l’heure est à la sobriété à tous les niveaux et revoir sa façon de voyager fait partie des priorités numéro une. Pas question toutefois de se priver de voyage : après deux ans de pandémie, on a plus que jamais besoin de se ressourcer et le voyage nous permet sans aucun doute d’accéder à un état de détente ultime. Mais alors,où partir sans que notre impact écologique ne nous fasse trop culpabiliser?

Paradis désenchanté

Et si on vous disait qu’il est possible d’en prendre plein la vue et de bénéficier des atouts des Maldives sans quitter l’Europe ? Vous avez du mal à y croire ? Sur Tik-Tok et Instagram, pourtant, une destination fait fureur : il s’agit de l’Albanie, située sur la péninsule balkanique au sud-est de l’Europe. Située à 2136 kilomètres de notre capitale, l’Albanie apparaît alors comme un compromis idéal pour ceux en quête de grands espaces paradisiaques. Sur les réseaux sociaux, elle bénéficie d’ailleurs désormais du surnom de “Maldives de l’Europe”.

C’est surtout la station balnéaire Ksamil, située au sud du pays, qui attire pour ses étendues d'eau à perte de vue. Sa plage est d’ailleurs considérée comme l’une des plus belles de l’Europe. Car la Riviera albanaise, c’est bien plus que 100 km de littoral, ce sont également des criques cachées et des sites archéologiques à couper le souffle. Depuis quelque temps, Ksamil est donc naturellement devenu the place-to-be et de nombreux hôtels de luxe qui rappellent ceux installés aux Maldives ont fait leur apparition. L’un des spots les plus en vogue ? Sans aucun doute la Pema e Thate beach, avec ses lits de plages à baldaquin qui surplombent la mer.

Si la destination séduit tant les internautes, c’est aussi pour son prix bien plus abordable que les Maldives ; pour une semaine de vacances à l’hôtel, comptez en moyenne 1 043 € pour deux personnes contre 2 718 € pour un séjour équivalent aux Maldives selon les estimations de Ou-et-Quand.net.. de quoi faire de belles économies sur votre budget vacances sans subir de décalage horaire. Alors, on attend quoi pour booker ?